Caroline Neal

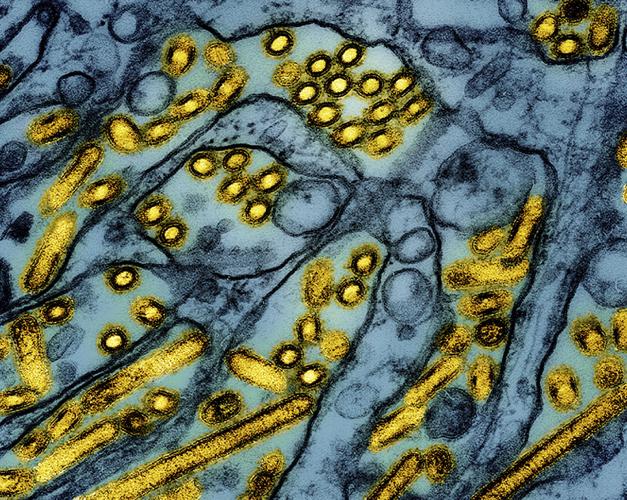

RACINE — Across the country, H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza, or avian flu, has spread among animals, affecting farms, zoos and wild birds.

As of Feb. 18, avian flu has affected 12,064 wild birds, 162,586,638 poultry, and 972 dairy herds since 2022.

Lindsey Long, a wildlife veterinarian at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, said the virus was first detected in Wisconsin in 2022, during which it impacted one wild bird and 10,220 poultry.

But the DNR has seen the virus re-emerge this winter.

“It’s important to realize that the CDC estimates the risk to the general public to be low from avian influenza,” said Dr. Darlene Konkle, Wisconsin state veterinarian and administrator at the Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. “We have been dealing with a strain of H5N1 influenza in North America and in other parts of the world now for several years.”

Avian influenza, she said, is affecting wildlife populations, including birds

|

| Konkle |

According to Konkle, Wisconsin has not seen cases in dairy cattle, but did have three cases in domestic poultry in December 2024.

Although avian flu has been around for years, this year is different, she said.

“(The United States has) seen more cases in domestic poultry earlier in the year than we did at the same time last year,” Konkle said. “The detection in dairy cattle in March of last year was also a detection in a new species. Whenever influenzas are detected in a new species, we pay attention and monitor those viruses really closely.”

In 2022, Long said cases were found in red fox, bobcat, fisher, skunk and otter.

“However, all of these weren’t considered transmitting to each other,” she said. “It’s because they were consuming waterfowl, likely that died from HPAI, so it’s not the same as the dairy cows where they’re transmitting it to each other.”

Though the risk to the general public is low, farms and zoos — including the Racine Zoo — are taking precautions.

Racine Zoo’s Dan Powell, curator of animal care and conservation, said staff had been expecting the virus to die down by now as avian flu usually peaks in the fall and spring.

“Usually, it correlates fairly well to the migration of other birds because they all group together for that migration,” he said. “Just like us, when it gets cold outside, we all huddle together, and then everybody gets the flu because we’re spending more time inside. They’re kind of the same way with their migration.”

With migration, he said, birds leave debris — such as fecal material, urine, food or bodies of birds that died from avian flu — which makes other animals susceptible.

When the virus didn’t die down this year, Powell said zoo staff members reviewed their safety practices.

Staff recently added a foot bath next to bird exhibits to clean their feet before entering.

“If you see the red tail hawk exhibit, there’s a keeper entrance door with a little vestibule, and right inside there, there’s always a foot bath or some booties to be able to put on for extra protection,” Powell said.

Two years ago, the Racine Zoo added tops to as many exhibits as possible so that fecal material from birds can’t fall into the exhibit, “which can be one of the major contributors to spreading the disease,” he said.

The zoo also put nets over the penguin exhibit to keep away ducks and geese, which would sometimes swim with the penguins.

In early February, the Milwaukee County Zoo closed its aviary to protect its birds from avian flu, but Powell said a similar step is not currently in the Racine Zoo’s plan.

“We don’t have an aviary similar to what they have, so we’re a little more spread out,” he said. “As it stands now, we don’t really feel like there’s too awful much that we need to do but definitely understand why Milwaukee made the decision they made.”

According to Konkle, separating species and increasing the distance between any domestic poultry or birds held in captivity from access to wild birds or their droppings is important.

“Each zoo is probably going to be a little different in how they assess their risk — because they’re all set up a little differently — and what they can do to increase their biosecurity and prevent introduction of disease,” she said.

Lately, Powell said, zoos have been focusing on the effects of avian flu on cat species.

“They’re quite susceptible to it, and it’s deadly to them as well,” he said.

Although preventing wild species from entering bird exhibits helps protect the zoo’s birds, avian flu can be introduced through the cats’ food supply.

“I believe the food supply for domestic cats and dogs, particularly the pelleted food, is considered very safe,” Powell said. “I can’t feed pelleted food to a tiger, and we can’t cook it. That makes it so that if it was present, then the virus would still be active.”

According to Powell, the United States Department of Agriculture recommendation for zoos is to feed animals meat that would have been for the human food supply.

The Racine Zoo confirmed with its food supply vendors that they follow the recommended practices.

“Essentially, the beef that we feed the lion or the tigers is the same beef that you would eat at home for your ground beef and that kind of stuff,” Powell said. “It’s just grabbed differently in the process and not as choice of cuts, and then cut differently so that it’s actually got a higher cartilage content.”

Racine Zoo staff also has maintained some of its COVID-19 safety practices, including wearing masks with the cats, primates and some birds, as well as monitoring their own health.

Powell said the zoo pays attention to the prevalence of the disease in Racine County and neighboring counties.

According to the DATCP, 96 birds from a backyard poultry farm were affected by avian flu in December 2024. Prior to December, there had not been a confirmed case in poultry in Racine County since 2022.

“My understanding is that birds that get it actually die really quickly,” he said. “The changes that we were making, or the things that we looked at early on, was in how we deal with found native species. So that instead of pulling those inside the building and then moving to another place for cremation or something like that later on, we just keep those separate.”

On Feb. 14, the DNR announced that laboratory tests confirmed H5 HPAI virus in a wild merganser collected in Milwaukee County.

It also received reports of sick or dead waterfowl, mostly mergansers, along the Lake Michigan shoreline in Milwaukee, Racine and Kenosha counties.

According to the DNR, the reports involved less than 50 birds.

H5 HPAI virus has been detected in Dane, St. Croix, Wood, Brown, Racine and Milwaukee counties since mid-December, with the majority of reports consisting of swans and Canada geese.

This winter, the DNR confirmed that the H5 HPAI virus was found in a Canada goose in Racine County.

Though a virus is more difficult to control when spreading among wild animals, there are response measures that can help keep domestic animals safe, depending on the virus, Konkle said.

For poultry farmers or residents with backyard chickens, Konkle said it’s important to keep the birds away from any wild birds or wild waterfowl and to use clean clothing and equipment when working with birds.

Long said residents, especially those with backyard birds or who come in contact with sick or dead wild waterfowl, should be aware of avian flu.

“In terms of mortality events with wild birds, we’ve still only been seeing a few birds involved in those,” Long said. “However, we know the virus is still circulating and can still be involved in environmental settings.”

No comments:

Post a Comment